Built by forty legionnaires over a few months in the late 1920s, the Foum Zabel Tunnel in Morocco remains the most spectacular demonstration of the know-how of Foreign Legion builders and the pure determination of a legionnaire to accomplish any given task.

Following the successful Rif War (1925-1927) in the north of what was then the French protectorate of Morocco, the French command turned its attention south to the High Atlas mountain range, located in the central part of the country. The large and hostile range represented one of the last refuges of the Moroccan insurgents. To facilitate its accessibility and pacification, an important road was to be built, running from north to south across the mountains.

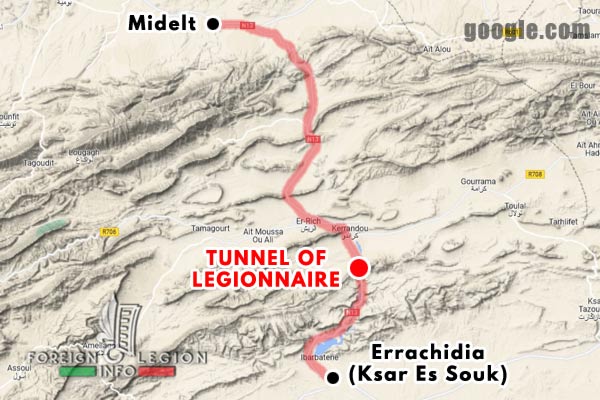

The new road, following the deep Ziz River valley and measuring almost 100 miles (153 km), would connect the towns of Midelt in the north and Ksar Es Souk (now Errachidia) in the south of the High Atlas.

From early 1927 onward, the enormous road construction works were carried out by the French Foreign Legion. In fact, the legionnaires had actively participated in the French pacification of Morocco since the very beginning in 1907, both as soldiers and builders, following in the footsteps of their ancient Roman predecessors. Thus, companies and battalions of the Legion’s 2e REI, 3e REI, and 4e REI took turns building the road. According to a French journalist of the time, “This was a gigantic task that no sultan of Morocco dared to realize.”

However, at milestone 111 (PK 111, point kilométrique) of the future road, there was a huge rocky spur of the Foum Zabel massif that extended straight into the river. It couldn’t be sidestepped; the mountain barrier had to be pierced. This task was assigned to a freshly constituted unit: the Sapper-Pioneer Company, 3e REI (CSP/3), under Captain Edard. The latter organized a detachment of three sergeants and forty legionnaires, led by Adjudant Michez (adjudant is equivalent to the rank of Sergeant First Class in the U.S. or Warrant Officer Class 2 in the UK), a veteran of the Legion who had already served with it in France during WWI. On July 24, 1927, the detachment arrived at the future construction site.

First, Adjudant Michez’s men installed their camp, with a solid wall around it to protect against eventual rebel attacks. Thereafter, they started their construction work. They had to dig the tunnel through the mountain of Foum Zabel and, moreover, build massive embankments on either side of the tunnel on which the planned road would run, each maintaining a gentle slope so that the trucks of the time could use them.

The technical equipment of the CSP detachment was very primitive. The legionnaires didn’t have hydraulic hammers, pneumatic drills or other modern means. Apart from explosives for basic drilling and blasting of the granite rock, the only tools they had at their disposal to pierce the mountain were sledgehammers, digging bars, picks, and shovels.

The actual excavation did not begin until October 1927. Yet, on March 6, 1928, at 4:30 p.m., the tunnel was successfully dug. For the rest of the month and throughout April, the detachment continued the construction of the tunnel and the sections of road leading to it from both sides.

In May 1928, the famous work was completed. At the time, the tunnel was about 203 feet (62 m) long, 20 feet (6 m) wide and 13 feet (4 m) high. Over 52,000 ft3 (1,488 m3) of granite rock had been excavated, not counting the thousands of cubic feet of rock removed on both sides of the tunnel to bring in the road.

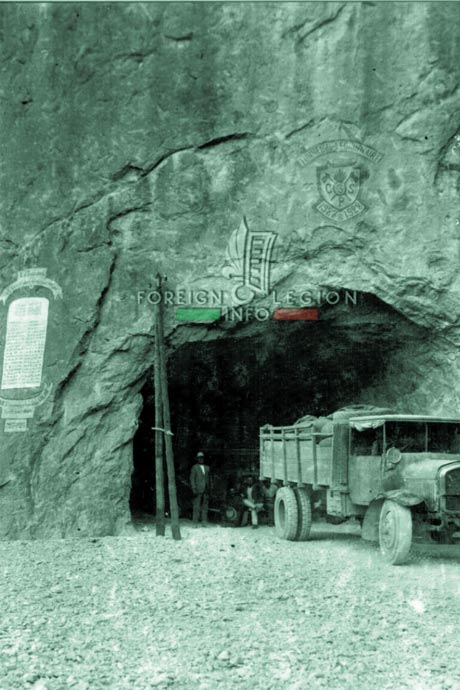

Above the southern entrance of the tunnel, on the rust-colored rock, was engraved a large insignia of the CSP/3 company with “Tunnel of Legionnaire” and “1927-1928” inscriptions around it; on the left appeared a tall plaque with the names of Adjudant Michez and his men who accomplished the difficult task. Above this plaque, there was an inscription: “The Tunnel was pierced in 6 months by 40 leg[ionnaires].” Under the plaque, one could read: “The energy of their muscles and a fierce determination were their only means.”

To the right of the tunnel’s northern entrance, under the Legion’s seven-flame grenade, there was a plaque with a simple and proud inscription: “The mountain was blocking our way. The order was given to pass regardless…. The Legion executed.” Under the inscription, the dates of the construction work were added: “October 1927 – May 1928.”

Despite extremely difficult working conditions, the detachment lost only two legionnaires. The first, Rauchert, was seriously wounded in late August. His leg had been torn off by a dynamite explosion and he died during his transfer to the hospital. The second, Hoffmann, died of dysentery in September.

The tunnel, along with the new road, performed its function perfectly and significantly aided in completing the pacification of the High Atlas and the rest of the isolated pockets held by the insurgents in Morocco, including those at the Bou Gafer. The new connection would also help the Ziz valley region to become prosperous.

Nevertheless, over the years, the tunnel has undergone changes, the first being the laying of asphalt. An important change occurred in the 1950s or 1960s, when the width at the foot of the tunnel was widened a little on both sides to allow the installation of new concrete barriers. Also, the left side of the southern entrance was slightly expanded, by less than two feet (0.5 m). Contrary to other sources of information, the height of the tunnel remained unchanged. These relatively minimal modifications once again demonstrate the timelessness of this monumental work.

Although the tunnel still serves the local population to this day, all the plaques, inscriptions and Legion symbols on the tunnel were destroyed after Morocco’s 1956 independence, in the context of the strong anti-French sentiments associated with it. However, what couldn’t be destroyed was the memory of the Legion’s glory among the Moroccans. From the late 1920s to the present, despite the mentioned sad times, the famous work still retains the nickname “Tunnel of Legionnaire” or “Tunnel of the Legion,” even on official modern Moroccan postcards and tourist maps.

The tunnel remains a symbol of the Foreign Legion and its legionnaires: their know-how, their skills, and their pure determination to achieve whatever task, regardless of its difficulty.

—

Related articles:

61st Engineer Legion Mixed Battalion

3e BMLE: 3rd Foreign Legion Task Force

1911 Battle of Alouana

1908 Forthassa Disaster